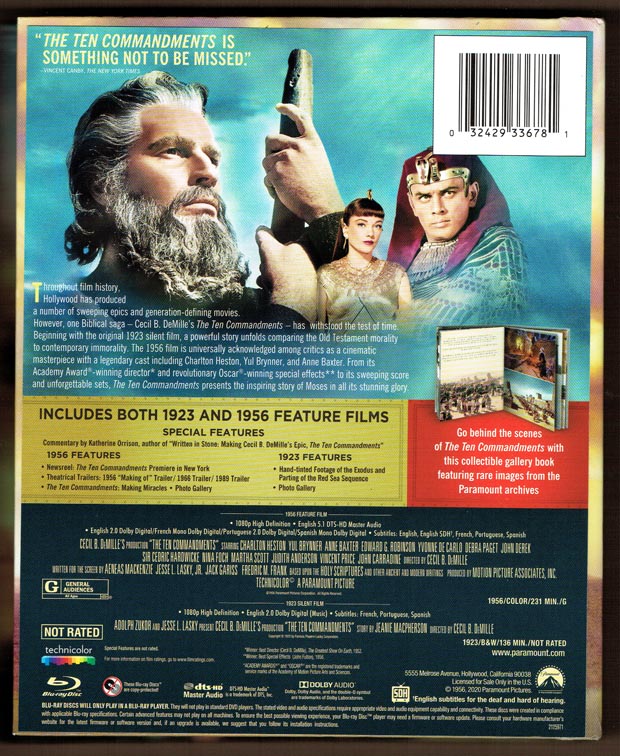

Ten Commandments 1956

Blu Ray "Digibook" edition released 2020

Review of the 1956 Ten Commandments Blu-ray

Digi-book extra: 1923 Ten Commandments (silent film)

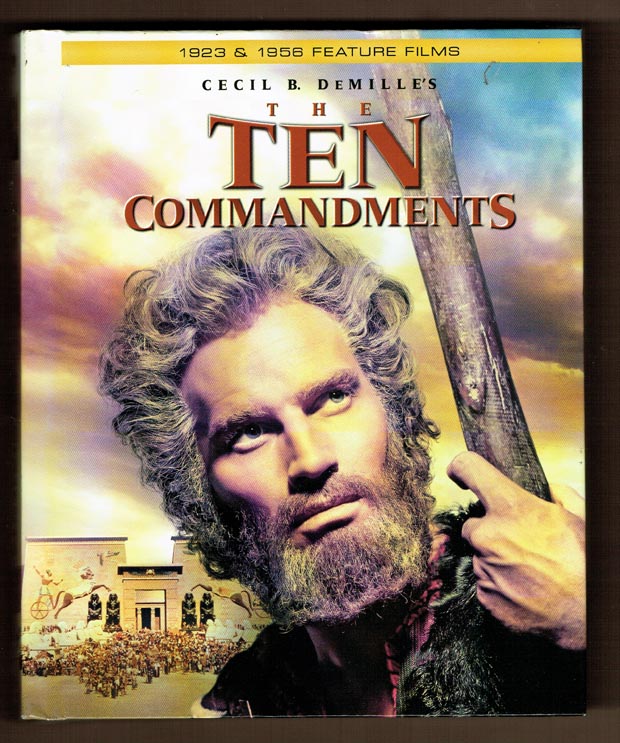

The "Digi-book"

One difference between this new Blu Ray release and the "50th Anniversary" DVD set is the new Blu Ray doesn't include the 6-part documentary on the making of the film that was included on the 2006 DVD, but the Blu Ray has a newer documentary titled "Making Miracles" which has new interviews and plenty of photography showing the film production (and cannibalizes pieces of the 2006 doc.) Both sets have the same audio commentary by Katherine Orrison who wrote the 256 page book "Written in Stone: Making Cecil B. DeMille's Epic The Ten Commandments" published in 1999.

The 1923 Silent Ten Commandments Blu Ray disc

I compared the 1923 silent film Ten Commandments "extra" that is packaged onto this Blu Ray Digibook version to the 50th Anniversary DVD set which is also included the 1923 silent version. The film is "silent" only in a relative sense: both the Blu Ray and DVD versions have a nonstop organ soundtrack. Not surprisingly, the Blu Ray version of the 1923 film is sharper than the DVD version. It isn't a huge improvement but it is discernible difference, supporting the idea here on this 2020 Blu Ray release that the 1923 version "extra" is a complete 1080 HD scan of that movie.

The 1956 Silent Ten Commandments Blu Ray disc

Comparing the 1080 HD version of the 1956 film with the DVD provides a much clearer difference. The HD Ten Commandments has sharp, bright colors and shows off Cecil B. DeMille's production with a lot of detail I'd never noticed before, such as Anne Baxter mouthing dialogue, unheard but probably understandable to a lip reader as her scene watching an off screen Heston fades into another scene where he is brought before the movie audience for the first time, kneeling before Cedric Hardwicke (as Egyptian Pharaoh Sethi) and Yul Brynner (as Rameses II). Another result of the high detail of the HD Blu Ray is seeing the fine small moles on Eddie Robinson's face, or the painterly body-makeup on Yul Brynner (is it makeup or just his tan? Supposedly, he was only in Egypt for one day for shooting because of commitments on the play The King and I. Of course, there's plenty of sun in California where Brynner's other scenes were shot). Besides odd items like that, there is the increased clarity to see the expensive art direction* which pervades so much of the movie.

DeMille spent a lot of time putting together this remake of his own 1923 film, officially beginning in May 1952 by telling Paramount executives his next project was Ten Commandments whether they wanted it or not, since he was willing to go to another studio to achieve it. DeMille was then seventy-one years old and had the kind of clout that comes from a long string of blockbuster movies and having a Hollywood name that was recognizable to most ticket-buyers despite the fact he wasn't an actor (perhaps only Hitchcock and Frank Capra compare in this sense).

A lot of the acting in the 1956 Ten Commandments looks overdone, but so much of what's on the screen from this large cast is all within the same range of emotion to each other (some exceptions might be the natural gracefulness of Cecil Hardwicke, Eddie Robinson, or the sinister Judith Anderson) so that it all works together in the same heightened way, like a very well-done comic book, or really, considering the context of the time it was made, like many of the melodramas of the mid-1950s that had a great deal of high-relief emoting.

After all, though the film purports to be a telling of the story of Moses from the Bible, it is actually fashioned like a 1950s inter-family drama about two brothers and their competitiveness and the 1950s anxieties of the women around them, with a subtext about communism versus democracy (for example, when Yochabel is going to be crushed by the slow-moving stone monument being put into place by the Hebrew slaves being whipped by Egyptian masters, it looks like this is DeMille's metaphor for tyranny vs. the individual, or even more so, USA/Western civilization vs USSR. In 1956 the contest between the two systems was a lot more serious, and undecided, than in the 21st century. Notice also in that scene that the artisan carver played by John Derek is the one who first swoops down to Yochabel's rescue.)

In the Ten Commandments, the Biblical elements are scrambled quite a bit. For example, Pharaoh drowns in the the Red Sea in the historical telling, but Yul makes it out alive in DeMille's version so that he can brood about it back at the Capitol of Egypt. That DeMille took a lot of liberty with the storytelling in order (apparently) to build up the box office potential of his subject meant he also watered down the Biblical chronology, which is a lot scarier than anything put on the screen in this film. (Speaking of scary, one of DeMille's later unrealized production ideas was to make a film version of the book of Revelation featuring the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse. How that could be made into a pleasing box office success for a mass audience seems impossible to me.)

Some facts about the Ten Commandments production:

The shooting script was 308 pages long and contained 70 speaking roles (take a look at the full cast at IMDB - you will be scrolling for awhile).

Five years in making, shot in Egypt (with up to 8,000 extras) and in Hollywood, with sets at Paramount spilling over into their parking lots and then spreading into the next door RKO lot. Right up until release, DeMille worried about whether the film would succeed and felt a lot of relief when it was a box office "juggernaut," at one time rising to the level of the #2 all-time earner behind perennial box office champion (adjusted for inflation) Gone with the Wind. DeMille's fear was that The Ten Commandments bombing could doom Paramount Studios.

It was a stressful shoot and DeMille had a heart attack during work in Egypt. Henry Wilcoxon** (cast in many DeMille movies, including Ten Commandments) was one of DeMille's closest friends and was there with him when it happened. He helped DeMille until medical attention arrived. Wilcoxon is in Ten Commandments on screen as Pentaur, and even directed some scenes while DeMille was convalescencing. DeMille's wife Constance Adams took over overseeing production when DeMille had his heart attack. Some directing was also done by cinematographer Loyal Griggs.

DeMille was back on the set after only three days from the heart attack, fearful that if news that he was incapacitated got out it could jeopardize the whole production, so he sat in a chair nearby while others followed through with his directions. The grueling work on the film picked up again later back in California. Constance began a descent into Alzheimer's before production was over, and several other key production people died. DeMille expressed the idea at the time that the film might not come out before his own death, which wasn't the case (he died in 1959). As part of his reaction to the huge success of the movie, he committed 10% of his profit sharing to distribution to the crew behind the film.

Another interesting corollary to Ten Commandments is that while DeMille is well known in Hollywood history for his support of the "black list" a number of "black-listed" actors and crew are in or worked on Ten Commandments (for example Edward G. Robinson and Elmer Bernstein.)

Amazon - Ten Commandments (1923 and 1956) Digibook [Blu-ray]

*Art Direction by Albert Nozaki, Hal Pereira, Walter H. Tyler. Set Decoration by Sam Comer Ray Moyer

** Even before production began on Ten Commandments while back in Hollywood, Wilcoxon seemed to be DeMille's one-man art support department because he could draw up ideas on paper on the spot while he and DeMille discussed production possibilities. Wilcoxon's behind-the-scenes influence is exemplified by the story bandied about in various versions that Heston's casting as Moses was because Wilcoxon saw that Heston's head and Michelangelo's statue of Moses in Italy showed a lot of physical similarity. Wilcoxon made sure that similarity came under DeMille's eyes while he was thinking about who to cast for the lead (Heston also appeared in DeMille's 1952 The Greatest Show on Earth).

What's Recent

- Grand Exit - 1935

- Island of Desire - 1951

- Road to Morocco

- The Devil and Miss Jones - 1941

- Sinners - 2025

- Something for the Boys - 1944

- The Mark of Zorro - 1940

- The Woman They Almost Lynched - 1953

- The Cat Girl - 1957

- El Vampiro - 1957

- Adventures of Hajji Baba – 1954

- Shanghai Express 1932

- Pandora's Box – 1929

- Diary of A Chambermaid - 1946

- The City Without Jews - 1924

- The Long Haul

- Midnight, 1939

- Hercules Against the Moon Men, 1964

- Send Me No Flowers - 1964

- Raymie - 1964.

- The Hangman 1959

- Kiss Me, Deadly - 1955

- Dracula's Daughter - 1936

- Crossing Delancey - 1988

- The Scavengers – 1959

- Mr. Hobbs Takes A Vacation - 1962

- Jackpot – 2024

- Surf Party - 1964

- Cyclotrode X – 1966

Original Page April 2020 | Updated April 2021